Keyboards: Masochism in Disguise

If you’ve ever learned a new language, you may have realised that doing so taught you so much about your mother tongue. Sentence structures, cases, tenses. These concepts leap from the subconscious mind into the critical part of your brain. Have you ever thought about how there’s even two ways to pronounce ‘the’, based on whether or not the following sound is a vowel or consonant?1

This article intends to spark a similar epiphany about a relatively mundane concept in comparison, the computer keyboard. You’ll learn how you’ve gotten used to the discomfort, and why it was so hard to learn to type when you were a child all those years ago.

We’ll begin with the first typewriter, and incrementally improve until we have reached something actually designed for the human hand. We’ll minimise the likelihood and severity of RSI, and increase comfort while we’re at it.

This article is written with the assumption that the reader is a standard home-row touch-typist, where the fingers rest on “ASDF” and “JKL;”. If you don’t type in this style, you will find much more comfort in learning this method than any improvement suggested below. I personally recommend typingclub.com as a great resource to learn.

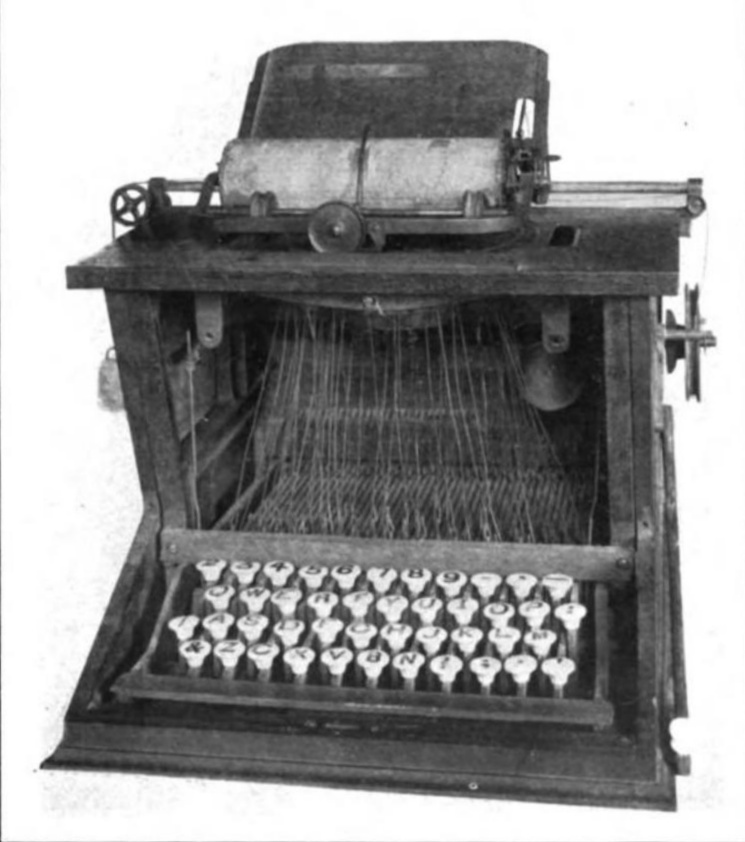

The year is 1868. Americans Christopher Sholes, Frank Hall, Carlos Glidden and Samuel Soule patent the first typewriter, the Sholes and Glidden Typewriter. It’s the first to have a QWERTY layout, and its commercial success causes QWERTY to become the de-facto standard layout for all following typewriters and keyboards2. This isn’t the only point I wish to flag - notably, the keys aren’t vertically aligned as there needs to be space to connect each button to its hammer with a metal rod.

I’ll come back to QWERTY. Let’s address this vertical alignment for now. Your fingers will comfortably bend over 180 degrees along their length, but they don’t really go sideways. Feel free to try getting more than even a 50-degree range of motion, but I suggest you do so outside a hospital. My point is keys should be aligned in columns, so we avoid that making that awkward diagonal travel as much as possible. There’s also no real reason to have differently-sized buttons, so we can do away with those too. With both modifications, we have (re)invented the ortholinear keyboard:

We’re already at the point where things are looking very alien. But don’t worry, this rabbit hole goes much deeper! You may have noticed that the above keyboard is missing a number row, numpad, navigation cluster and function keys. That’s because this is a 40% keyboard, meaning the number of keys on the physical device is 40% of that of a traditional keyboard. We access those keys through a concept called layering.

You’re already familiar with the idea, you just don’t know it. The shift key on your keyboard serves no purpose on its own, but holding it down changes the output of every other key on the device. Letters become capitalised, numbers are replaced with symbols and so on. We could say that by holding down the shift key, we are temporarily moving to the shift layer. Now, we extrapolate this idea. Imagine a second shift key, let’s call it ‘swap’. Much like shift it has no behaviour on its own, but modifies the behaviour of other keys. Swap + Q can be our ‘1’ key, swap + Y is ‘6’, you get the idea. Indeed this is exactly what the pictured keyboard is set up to do, you’ll note there is a swap (“raise”) key to the immediate right of the space bar. There’s also a “lower” key to the left. We can have an arbitrary number of layers, as long as we have a way to access them.

“But why bother with this?”, you may find yourself asking. “What’s wrong with having more buttons?”. As I addressed at the top of this article, we are reducing the impact of RSI. If you’re one of the 60-80% of people in the developed world who primarily conduct their work at a computer, this impacts you and is a real health concern. You should be avoiding awkward finger movements. Having fewer buttons necessarily means everything can be closer to your resting home row position, and therefore more natural to reach. There’s certainly a balance to be struck, but the current standard is way off.

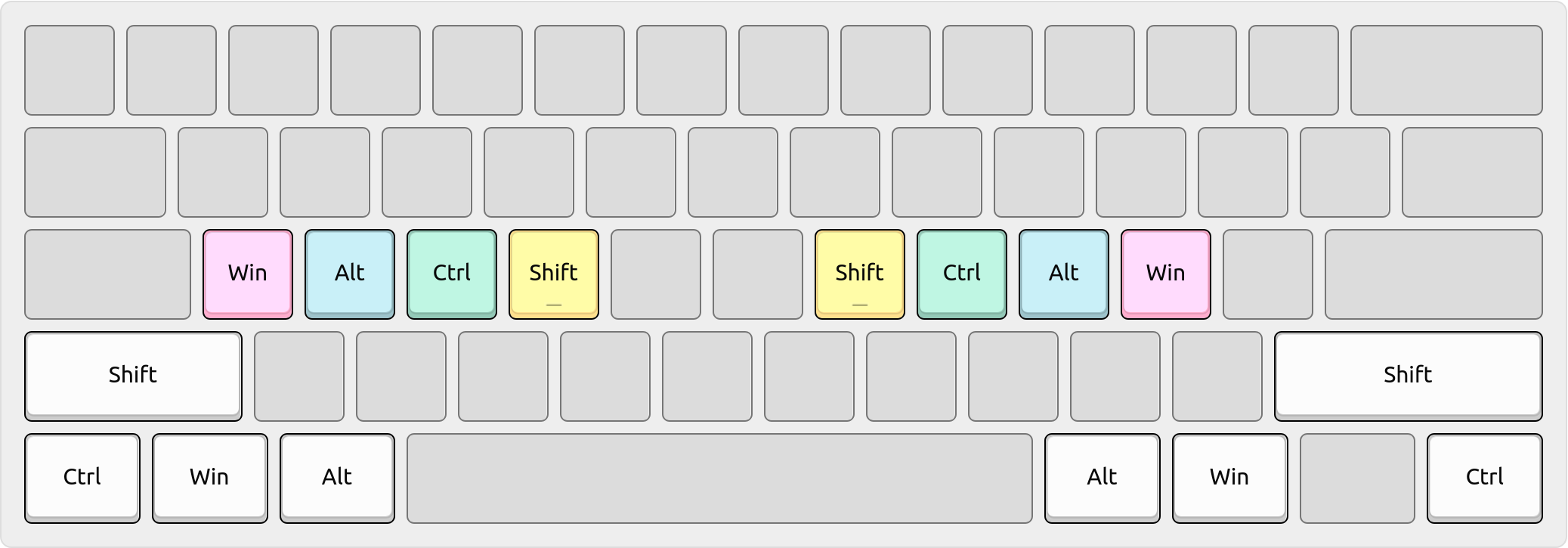

So, in this pursuit to get rid of buttons, I’m going to make things even crazier. What if I told you we don’t need dedicated keys for shift, ctrl, alt & friends? Enter hold-tap behaviour. It’s 2024, keyboards can be programmed to do different things if their keys are tapped, or held down3. With this new dimension to expand in, we could make letters capitalise themselves if we hold the key for longer than 200 milliseconds. In practice, this would be slow, so let’s retain the idea of a shifting key, but simply put it on a letter key. For example, holding down the q key could capitalise every other letter key. We’d need a second one of these if we ever wanted a capital ‘Q’, so let’s put that on the other side of the keyboard, on P. We’ve now made the left and right shift keys redundant, and we can remove or repurpose these keys too. The next improvement is to actually do this with F and J, instead of Q and P, so we don’t even need to move our fingers to hit the shift key. We can do something similar with all of the home row. We’ll call these our ‘home row mods’:

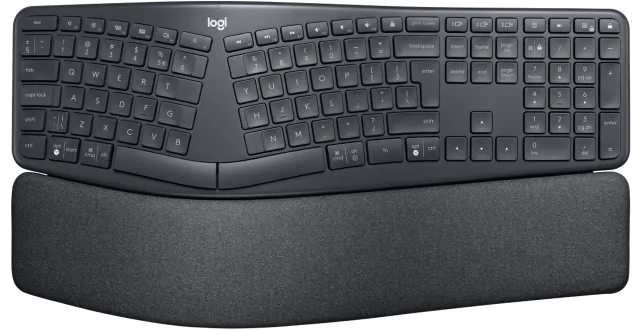

Let’s address wrist pain. It’s generally agreed that having your wrist bent outwards towards your pinky for an extended period is unhealthy. Easily solved, just move the keys to your hand so you can reach all keys without bending your wrist.

There’s nothing stopping us from splitting the keyboard into two free halves that can be oriented however you wish.

Let’s put it all together. A split keyboard, in an ortholinear layout with minimal numbers of keys:

I lied! That’s not ortholinear - the keys aren’t in a grid. This variant is called a column-staggered layout and takes into account the differing lengths and natural positions of your fingers. You’ll also notice the oddly placed buttons in the bottom corners. These are the thumb clusters. Placed to be as comfortable as possible to reach, this design gives your strongest finger more to do. The thumbs on a traditional keyboard are almost entirely wasted, used for space and maybe the occasional ctrl or alt press. We can place frequently-used keys like our backspace and enter here, taking these keys from being awkward to reach with your weakest finger, to being placed right under your thumb. Typically, layer keys are placed in the thumb clusters too.

There’s only a couple easy improvements left to make before I begin my QWERTY slander. When bending your finger, your fingertip traces a curved path. Knowing this, let’s raise the furthest keys to construct a bowl shape, which means we need even less movement to reach further keys.

And lastly, something called ‘tenting’. It’s not totally necessary and not everyone likes it, but you can raise the thumb side of the board to create a more natural angle for your hands to rest at.

We’ve reached a point where the device pictured is barely recognisable as a keyboard. It looks more like something you’d pilot an alien spaceship with. Some take things to the extreme, with blank keycaps or attaching the things to your armrests. There’s a lot of experimentation to be done, and everyone’s optimal setup is going to be different.

Why QWERTY sucks

In the English language, the three most common letters are E, T and A. In the QWERTY layout, you need to move your fingers to reach these keys. Meanwhile, K and J respectively make the 5th and 4th least-used letters, yet for some reason these live on the home row. Madness. I do not wish to even comment on the semicolon key, for I cannot do so without a lot of impassioned swearing.

55% of typing is done on the top row, while the home row only sees 30%. Over two-thirds of the time, you need to move your finger to a different row to hit the key you want. Cumulatively, the seven QWERTY letter keys that your fingers rest on comprise 26% of your typing. To give you a sense of just how bad that is, if we set these 7 keys to just be the top 7 most frequent letters instead, we get up to 58%! Moving the semicolon key elsewhere, we can add another letter, reaching 64%. Yes, it’s possible that two-thirds of your typing can be done without moving.

There are other optimisations to consider though. For example, we want to minimise making one finger do a disproportionate amount of work when typing a single word. Consider the word ‘unjust’, four of the six requisite keypresses are done by the same finger. Also, we want common two-letter sequences (“bigrams”) to be comfortable to type. For example, it would be unacceptable to have to type Q and U, or T and H with the same finger. There are a lot of metrics to consider. This stuff gets very complicated - for example, the sequence ‘ll’ is disproportionately common when compared to the relative frequency of the letter L itself. That is to say, it is weirdly common for ‘L’s to appear in pairs when analysing all ‘L’s in typical English. Does that mean we should put L in a more accessible location?

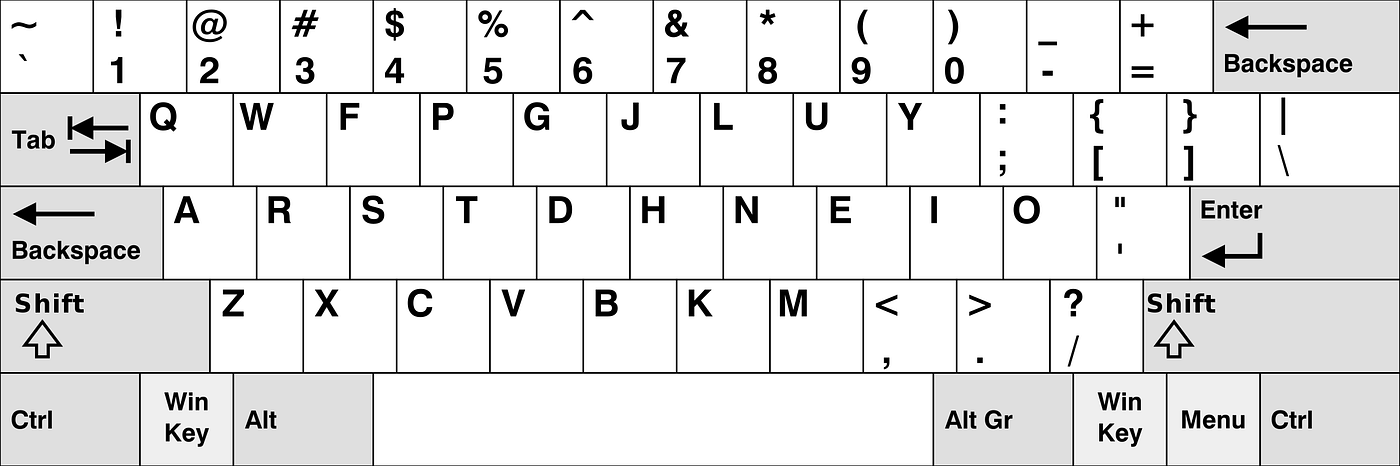

Luckily, a lot of very clever people have already done this difficult analysis for us. There is a whole world of alternative keyboard layouts, but the most prevalent are Dvorak and Colemak (and its popular variant, Colemak Mod-DH).

You’ll immediately notice that the most common letters have been moved to the middle row, but we retain the convenience of common shortcut keys remaining in place in the lower left (ctrl-z and friends). Another improvement to note, the relatively useless caps lock key has been replaced with a second backspace, which is more easily reached than a typical backspace.

The biggest drawback to this is that you already know QWERTY and relearning muscle memory is hard. It can take weeks, months or even years to get to the point where you are as comfortable on a new layout as you were on QWERTY. Even worse, in doing so you can lose competence on normal layouts. It’s certainly not for everyone. Me? I’m learning Colemak-DH, and will eventually switch to it full-time. It’s extremely infuriating, but by god is it so much more comfortable.

There are dozens of behaviours you can assign to keys. Hundreds of standard keyboard layouts. Thousands of differently-shaped keyboards. I hope I’ve helped you realise just how badly typing sucks currently, and I hope I have given you the courage to break free from its carpal tunnel-strained grip.

-

“The paper, the alphabet. The dog, the oven.” It’s not totally ubiquitous, but most speakers will say something more like ‘thee’ when preceding a vowel sound to avoid the mildly uncomfortable glottal stop. Man, I totally would have studied linguistics if I wasn’t into computers. ↩

-

There are competing theories as to exactly how and why the QWERTY layout was invented. This paper aims to explore the real reasoning. ↩

-

At time of writing, complex behaviour like this is usually achieved with either QMK or ZMK keyboard firmware. Here’s the ZMK documentation for hold-tap. ↩